Humbaba (or Huwawa)

We're interested in this character for a couple reasons, and mainly because just as Gilgamesh seems a ur, archetypical or proto hero, so too Humbaba is passed on to us throughout "epic" history or narratives.

Humbaba And Medusa

Although the connection is both abstract and unclear, Sumerian

Humbaba is believed to have morphed into the Greek Medusa. Most notable is that

masks of boths are frequent in either culture (and cultures that borrowed from

both), and the masks are nearly identical. Both Humbaba and Medusa's head's are

never shown in profile and always full-frontal.

Humbaba:

Greek Medusa coins (350-450 BCE):

Beheading both is the key movement of each story, and both Gilgamesh and Perseus place the head in a leather bag. Both are also divinely guided in the battle.

In Greek mythology, killing Medusa creates the winged horse

Pegasus. A similar creature exists in Sumerian mythology as "The Bull of

Heaven", or a gryphon: winged mammal:

Louvre, Paris

Athena keeps a mask of Medusa on her shield, and the Italian island Sicily (long a Greek island), uses the mask of Medusa as its emblem and flag (neither of these are relevant to much but are cool!).

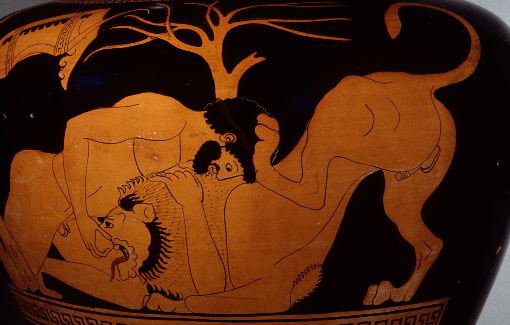

Humbaba As A Lion

Just as the "unicorn" was no doubt really someone's description of

a rhinoceros, and Satan is rooted in Dionysus, Pan and Satyrs (more on that

later), and the Cylopes were in fact the fossils of Sicilian pygmy elephants

(more on that later), Humbaba (and Medusa as well) is believed to have been

based on the description of a lion. So again we see that there are often

kernels of factual truth to our "monsters".

London's British Museum features a number of rooms displaying the importance of ritualized lion hunting in Assyrian culture. In true superhero style, the Epic of Gilgamesh suggests that this was some sort of hand to hand combat, man against animal, but the museum's carvings show us that it was more akin to organized group warfare and, as was likely nearly always true in ancient societies, the hunt served as preparation for war.

Gilgamesh and Hercules

In Greek

mythology, Hercules' first labor is to kill the Nemean Lion. Like

Gilgamesh following Enkidu's death, Hercules is also commonly represented as

dressed in a lion's skin. Hercules' eleventh

labor is to descend to the underworld to retrieve magical golden apples that belonged

to Zeus, in a tree protected by a serpent, in a faraway garden.... After a

long journey to the ends of the world and some mighty battles, Hercules

succeeds, but the apples must then be returned to the gods.

Humbaba As the "Other"

The Sumerians were, we believe, some of the first people to develop a set of written laws, Code of Hammurabi, that governed the behavior of all their people. These are believed to be the precursor to the Jewish Decalogue ("Ten Commandments") and considered a major step in the evolution of human society; when we speak of the US as a nation of laws, we trace our cultural heritage back to this revolutionary idea. Like most moral codes, Code of Hammurabi explicitly bans both murder and theft.

It's clear from the story that Humbaba really poses no threat to Uruk but that he guards the sacred cedars, which would be a very valuable commodity in a place like Iraq (ancient Sumeria/Mesopotamia etc) that didn't, and still doesn’t, have its own supply of timber.

So how can a law-governed community -- like Uruk, or any other law-governed country -- justify invading and stealing the natural or human resources of another community or country, especially if that country poses no explicit threat?

The easiest and, history proves, traditional means is to “Other” that community: to make them less than human and thus not protected by one's laws. In other words, if my laws state that I cannot kill or steal from another human being, then I can pretend like the tribe across the river is not human. Or, more recently, if my laws say “we hold these truth to be self evident, that all men are created equal,” then the only way I can justify enslaving a class of “men” is to deny that they are, in fact, actually men.

Humbaba, then, is treated as a

monster, rather than as a man or a human, and we find that in Humbaba

Sumerian "monsters" possess the same qualities still employed today. Monsters:

1) Possess some human traits (he isn't just an animal)

2) Possess super human traits (he isn't just a human)

3) Have physical qualities that make the monstrosity easily

apparent; we can

visibly see he isn’t like us

4) Can only be killed by a hero; in fact the hero cannot be the

hero unless he kills the

monster; so killing the monster often defines heroism

6) Possesses the same qualities as the hero or in fact represents

qualities respected by

the same people that make him a monster (see:

Hubris)

In short, by calling him less than human, Gilgamesh justifies invading Humbaba's country and stealing Humaba's (or H's country's) cedar.

The debate about whether Gilgamesh is justified executing Humbaba is, of course, central to the story, as it leads to Enkidu's death.

Polytheism and the Other:

Punishing Gilgamesh and Enkidu for Humbaba's killing also reminds us that in polytheistic, vs. monotheistic, societies, the Other (the "monster", the foreigner) are also protected by viable gods. We'll note that later, both the Acheaens ("Greeks") and Trojans are protected by the same pantheon, with different gods favoring different peoples, and in The Odyssey Odysseus and his men are punished for wounding the Cyclops, Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon.

This will change with the rise of monotheism, in which a people see themselves as either singularly chosen or as the only people whose god is either real or "good".

We will follow this relationship between the hero and the Other throughout the semester.