| Asian American Comparative Collection (AACC) University of Idaho 875 Perimeter Drive, MS 1111 Moscow, Idaho 83844-1111 USA 208-885-7075 |

Priscilla Wegars, Ph.D., Volunteer Curator pwegars@uidaho.edu Renae Campbell, M.A., RPA, Research Associate rjcampbell@uidaho.edu |

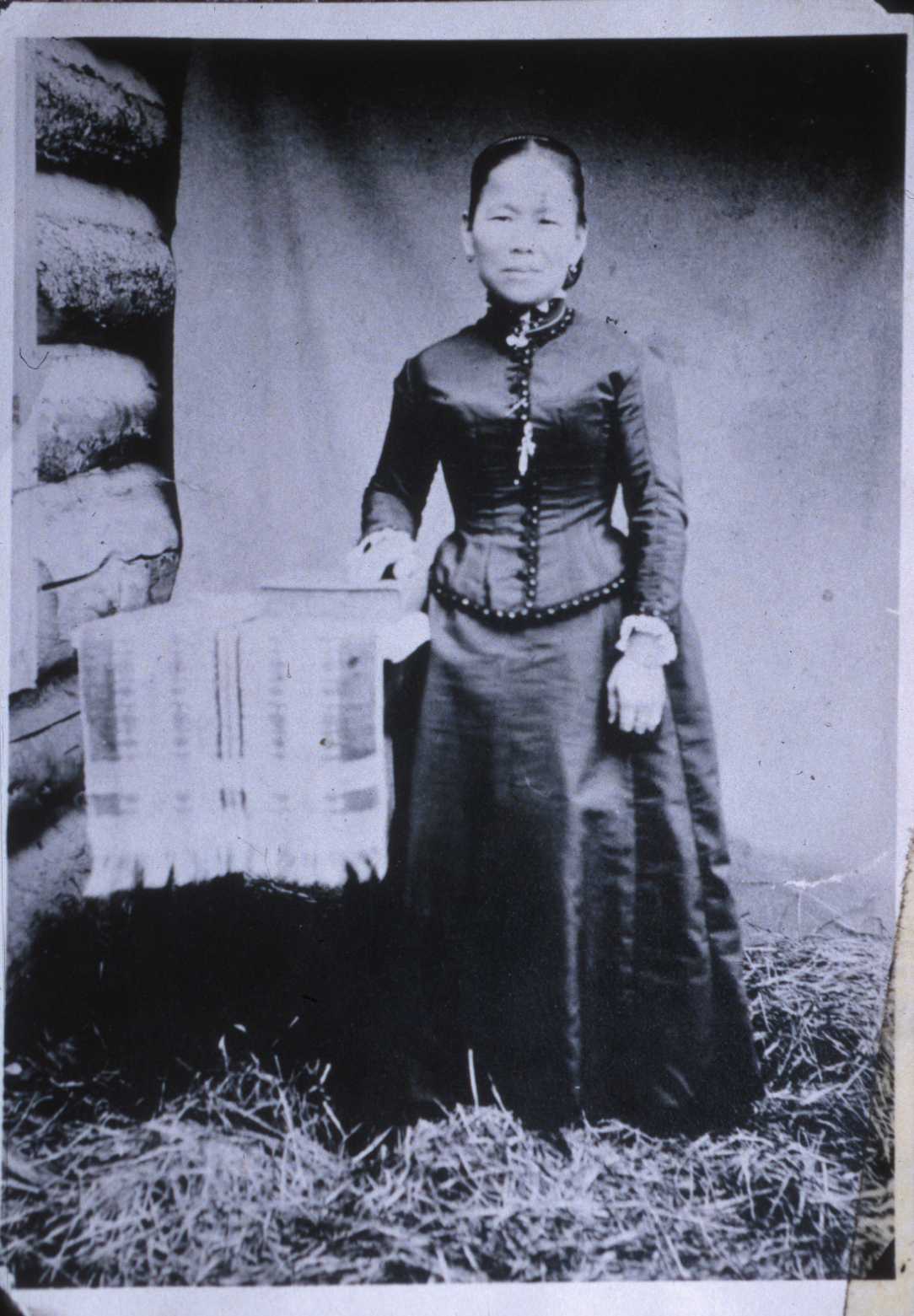

Polly Bemis's life has been greatly romanticized by many people who have written about her. There is no evidence for the truth of the most persistent legend, that she was "won in a poker game." As she neared death in 1933, both Polly and C. J. Czizek, "one of her most intimate friends from the Salmon country," vehemently denied the rumor.

Another common misconception, not in McCunn's book, is that Polly Bemis was once a prostitute. Again, there is no evidence for that assumption. Although a Chinese resident of Warrens (now Warren), Idaho, paid $2500 for her, and had her brought to that community by an old Chinese man (alas, not the handsome, young "Jim" of book and movie), Polly's owner undoubtedly purchased her as his concubine. In China at that time, a wealthy man might have one or more wives, plus one or more concubines, all living in the same household. Our term "mistress" most closely approximates the term, but it does not equate with the concept as it existed in China, where a concubine held a legally-recognized position as a family member, and whose children were considered legitimate offspring of the man and his primary wife.

Chinese custom decreed that if a man immigrated to the United States to work, his wife should remain at home in China to look after his parents. While abroad, however, he might take with him, or acquire, a concubine to perform "wifely duties" (see, The Concubine's Children, by Denise Chong). A Chinese man fortunate enough to have a concubine would not use her as a prostitute because he would "lose face" through sharing her with others.

Other myths about Polly include the

use of the name "Lalu Nathoy" for her; there is no evidence for

that being her name. Also, there is no evidence that her owner's

name was "Hong King."

We do not yet know how Polly managed to extricate herself from her Chinese owner; perhaps he died. Whatever happened, it occurred before mid-1880 since that year's U.S. Census lists her as living with, but not married to, Charlie Bemis. In September 1890 a "gambling affray" resulted in Bemis being shot. He hovered near death for some time, and Polly nursed him back to health. They married in 1894, and moved down to the Salmon River where they took up a mining claim, not a homestead, as is commonly believed.

For over two decades Priscilla Wegars collected documentary information about Polly Bemis in preparation for several, more accurate, works about her life. They include Polly Bemis: A Chinese American Pioneer (2003), a brief biography for 4th graders; the lengthy chapter "Polly Bemis: Lurid Life or Literary Legend?" in Wild Women of the Old West, edited by Glenda Riley and Richard W. Etulain, 45-68, 200-203, (2003); and Polly Bemis: The Life and Times of a Chinese American Pioneer (2020). Wegars has also taught a summer school/enrichment class for the University of Idaho in which participants compare both the book and the movie with what is known about the real Polly Bemis, while visiting Polly's restored cabin, now easily accessible only by jet boat. For more information about this class, see Tours. A slide lecture is also available, as are Lessons for 4th graders based on the book. A recording of Priscilla Wegars' slide lecture on Polly Bemis, presented for the Lemhi County Historical Society and Museum on February 10, 2021, can be viewed on YouTube.

Scheduled PowerPoint

Presentation with Book Signing:

None currently scheduled.

Please email pwegars@moscow.com

to schedule a PowerPoint presentation and/or a book signing.

During Priscilla Wegars' extensive research on the Chinese in the West, she has never found any documentation or substantiation for these rumored "Chinese tunnels." In cities where the Chinese owned buildings and utilized the basements, the latter may have been subdivided or partitioned into smaller areas as living quarters or opium-smoking establishments, with hallways, but these in no way can be considered "tunnels."

In Lewiston, Idaho, for example, Erb Hardware Company President Jeanine Bennett graciously led Wegars on a tour of the store's basement areas, in response to a local newspaper's suggestion that it contained entrances to such "tunnels." Instead, the arched openings actually lead to passageways under the sidewalk (today either in use as storage areas, or blocked up) that were once used for delivery access, or to admit light. The architectural term for these passageways is "sidewalk vaults."

Although the sidewalk openings (metal doors) or glass blocks to allow light (round or rectangular; eventually colored purple by the sun), no longer exist in the sidewalk around Erb's, they can be seen in the sidewalks of many towns and cities throughout the West. The passageways underneath them are simply access channels, and have no connection with early Chinese residents. The same can be said for the so-called "Chinese tunnels" rumored to exist in Boise and Pocatello, Idaho; Baker City and Pendleton, Oregon; Seattle and Tacoma, Washington; Victoria, BC, and many other places.

Wegars would appreciate receiving

information about other communities with rumored "Chinese tunnels"

and would especially welcome descriptive information from anyone

who has visited what they were told was a "Chinese tunnel."

Chinese tunnel myths are often perpetuated through tourism and

mass media. In Pendleton, Oregon, for example, the "Pendleton

Underground" tour takes visitors into basements that some guides

call "Chinese tunnels." Although there was apparently once a

Chinese laundry in one basement, there is convincing evidence to

indicate that any other Chinese people once lived "underground"

there. See the Oregon

Encyclopedia for a debunking of this particular myth.

For more information on this topic,

please see Priscilla Wegars' article, "Exposing Negative Chinese

Terminology and Stereotypes," Chapter 4 in Chinese Diaspora

Archaeology in North America, ed. Chelsea Rose and J. Ryan

Kennedy, pp. 83-108 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida,

2020).