ANIMALS ARE PEOPLE, TOO:

OVERCOMING THE MYTH OF HUMAN UNIQUENESS

By Nick Gier, Professor Emeritus, University of Idaho

nickgier@roadrunner.com

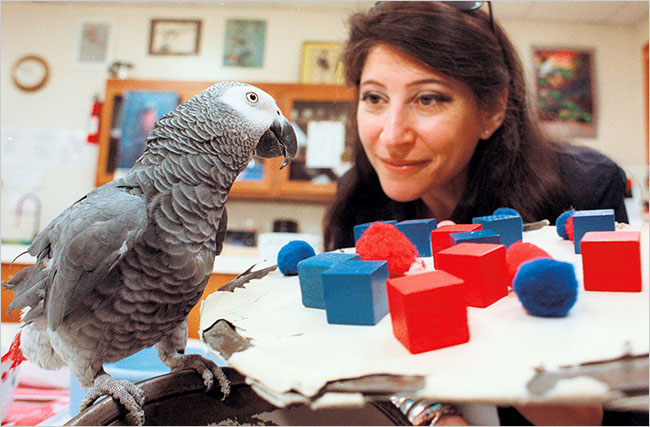

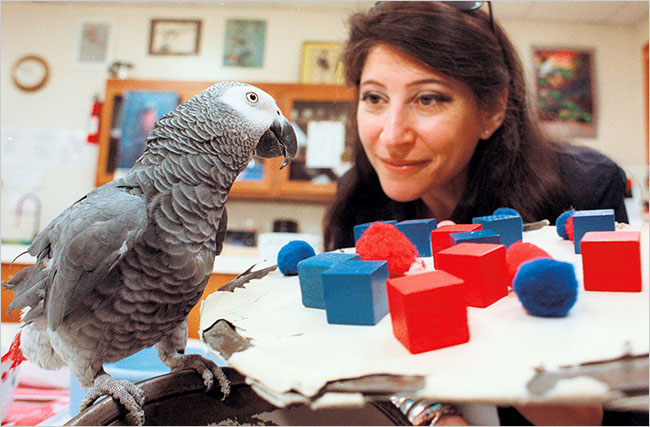

Alex and Irene Pepperberg

Go to www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/AnimalIntell.htm for the image

There were many brilliant students in Plato's Academy, Europe's first university, but Aristotle was by far the most famous. Coming down to Athens from the barbarian north when he was 18, Aristotle eventually wrote classic works on ethics, political philosophy, and metaphysics. He also had the privilege of being the tutor of Alexander the Great.

In his book On the Soul Aristotle proposed that there were three types of souls, and the human fetus evolves organically from one to the next. During the first trimester the fetus is a "nutritive" soul, a life principle that we share with animals and plants. After three months the fetus develops a "sensitive" soul: it now has the capacity, unlike plants, to move and to perceive.

After six months the human fetus adds a "rational" soul on top of its nutritive-sensitive base. (Explosive fetal brain development from 25-33 weeks confirms Aristotle's speculation on this essential point. See fetal brain slides at <www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/fetalbrain.htm>.) This is a faculty that humans share only with God, and this makes them superior to all the other beings on earth. Only God and humans can be called persons; and only they can be moral and spiritual beings.

The Catholic Church adopted Aristotle's doctrine of the soul, including his sexist outrage, based on no evidence except his own bias against women, that female fetuses lag 80-90 days in their development and therefore never acquire a proper rational soul. The authority of one Greek philosopher was used to support patriarchy's oppression of Euro-American women until the last century!

For nearly 2,400 years this view of human uniqueness has dominated Judeo-Christian religion, morality, and law. Aristotle's influence is seen in St. Augustine's view that the abortion of a first trimester fetus was not murder, and St. Aquinas' belief that the fetus did not become a person until late in pregnancy. Canon law on this essential point was not changed until 1917. For more see "Abortion, Persons, and the Fetus."

Many cracks have begun to appear in the hard shell that has enveloped the claim of human uniqueness. Dolphins have 40 percent more neo-cortical area in their brains than we do, and they have rich emotional and mental lives. At the Dolphin Institute in Hawaii, Louis Herman has taught his four dolphins to understand sign language. One day Herman asked two of them to make up a new trick on their own. The two dolphins dove and within seconds exploded out of the water, circling on their tails, and spouting water like synchronized fountains.

Although the idea was rejected for many years, a persistent woman scientist finally convinced her colleagues that African elephants do in fact transmit complex signals over long distances by means of seismic waves. Dozens of unemployed Asian logging elephants now have second career as painters. Most of the paintings are abstract, but trainers have taught them to depict natural scenes as well. Most amazingly, some have actually done self-portraits. Selling for $350-$750 each these pachyderm painters have raised $100,000 for elephant rehabilitation.

The mental and emotional achievements of our primate cousins are well known and so impressive that the Chimpanzee Collaboratory has formed to promote chimp personhood. As Harvard lecturer Steven Wise argues: "If a human four-year-old has what it takes for legal personhood, then a chimpanzee should be able to be a legal person [too]." In addition to learning sign language (including making up new words) and teaching it to their young, chimps have been observed making tools and using herbal medicines. In a fairly simple computer memory game, a chimp, seemingly without much concentration, can remember all nine numbers in a random sequence while the sharpest human subjects remember only one or two.

If Aristotle were come back for a visit today, he would advisedly make an amendment to his theory: chimps, gorillas, dolphins, and whales are persons and as such have a serious moral right to life. But Aristotle would face clear defeat if he to had to face the evidence of Irene Pepperberg's animal superstar. Pepperberg's African Grey parrot Alex had the proverbial bird brain--the size of a peeled walnut--but over 31 years she carefully documented an amazingly rich mental and emotional life. Under strict laboratory conditions Alex, when asked to combine seven colors, five shapes, and four materials, could identify 80 different objects.

Just like Washoe the Chimp, who called ducks "water birds," Alex made up "yummy bread" for cake. Because one needs lips to say a "p," Alex improvised for an apple calling it "banerry," a combination of banana and cherry. While in the laboratory with other parrots, he was constantly criticizing the others for their poor pronunciation, repeatedly saying "speak more clearly!" Emotionally, Alex would respond to Pepperberg, not repetitively or arbitrarily, but specifically and appropriately, such as "What's your problem?" and "I'm going to go away now." His last words to the love of his life were "You be good, I love you."

A recent experiment with dogs did not require language for scientists to conclude that they had a sense of fairness. At the Clever Dog Lab at the University of Vienna, scientists placed two dogs side by side and commanded them to offer a paw. Initially, one received a piece of sausage for the correct response, and the other got a piece of bread. When the reward was withdrawn from one dog, she not only stopped offering her paw, but turned away from the scientist in disgust. As opposed chimps placed in the same circumstances, the Austrian dogs did not perceive the vegetarian option as a slight. Primatologist Frans de Waal has also found that a capuchin monkey refused to trade pebbles for pieces of cucumber when his companion was given a grape instead for the same task.

The more we learn about insect intelligence, the more amazing it becomes. Research about the swarming of bees, traditionally used as an example of mindless behavior, has demonstrated that new hive sites are chosen by what the researchers called "robust consensus." This decision making was based not only on information sharing but also independent verification. (Studies of how ants, operating as E. O. Wilson's superorganism, choose new nests by similar methods.) The same issue of the journal that published article on bee decision making also contained an article about how party line thinking in the British Parliament (transferred to many other countries) was embarrassingly mindless. (See The Economist, Feb. 14, 2009, pp. 89-90.)

In 1992 while on sabbatical in India I gave up eating beef, pork, and chicken. My decision was based primarily on a choice of a healthier diet rather than any strong belief in animal rights. For a long time I indulged in big brain species chauvinism and allowed apes, gorillas, dolphins, and whales into the sacred hall of persons, but now I have no good reasons to draw a line between Washoe and Alex. This new evidence for animal personhood should force all of us to rethink what is now become the Myth of Human Uniqueness.