SHOULD THE HEAD OF NEFERTITI AND

THE ELGIN MARBLES GO BACK HOME?

By Nick Gier, Professor Emeritus, University of Idaho

nickgier@uidaho.edu

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne'er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch'd thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

---Lord Byron on the removal of the Parthenon Marbles

Once again the Greek government has demanded that the Parthenon Marbles, better known in imperialist circles as the Elgin Marbles, be returned from the British Museum to their rightful owners, the Greek people. The stunning new Acropolis Museum has just opened, and there is a gallery where a plaster copy of half the famous frieze waits to be replaced with the original.

Just in time for the grand opening, Italy's president was present to return the foot of Artemis that was part of the frieze. The Vatican has repatriated another foot of a lyre player on the frieze, and a Heidelberg museum has given back the head of a young man. In addition to these fragments, 25 other major pieces have been voluntarily repatriated to the Acropolis Museum. The unrepentant British, however, still have 247 feet of the original frieze, 15 metope panels, and 17 statues. Christopher Hitchens describes the absurdity of the situation: "The body of the goddess Iris is now in London, while her head is in Athens. The front part of the torso of Poseidon is in London and the rear part is in Athens. This is grotesque."

Noting that the Greeks had previously been amenable to a generous loan policy, the British journal The Economist states that "the Greek government risks driving museums everywhere into clinging to their possessions for fear of losing them. If the aim is for the greatest number of people to see the greatest number of treasures, a better way must be found."

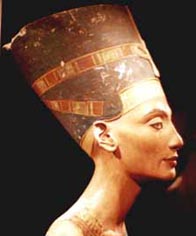

In 1801 Lord Elgin did get permission from the Ottoman authorities, but the legality of this transaction has been disputed. Many other famous museum collections, however, do not have even a veneer of lawful justification. During the excavations at El Armana from 1911-14, Ludwig Borchardt of the Imperial German Institute for Egyptology pulled off one of the most amazing deceptions in the history of archaeology. Borchardt had found the head of Nefertiti, considered to be the one of the most beautiful examples of ancient Egyptian art.

Borchardt was determined to

have Nefertiti for the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, where she now resides. He

prepared a doctored photo of the bust that put it in the worst possible light,

and then described it to Egyptian authorities as a plaster bust rather than the

painted limestone that it actually is. The German agreement with Egypt was

based on an equal division of the Armana artifacts, so in exchange for

Nefertiti, Borchardt offered a painted stela of Pharaoh Akhenaten, Nefertiti,

and their children, an intimate family portrait unique to the Armana Period.

Early on it was clear that the total exchange of artifacts was not equal,

but more outrageous is the fact it has now been proved that the stela of the

royal family is a rather clumsy fake. Deepening the irony, Borchardt had gone

to great lengths to describe the fake as not only better than a similar one the

Germans had in Berlin, but also aesthetically superior to Nefertiti's bust.

Borchardt was determined to

have Nefertiti for the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, where she now resides. He

prepared a doctored photo of the bust that put it in the worst possible light,

and then described it to Egyptian authorities as a plaster bust rather than the

painted limestone that it actually is. The German agreement with Egypt was

based on an equal division of the Armana artifacts, so in exchange for

Nefertiti, Borchardt offered a painted stela of Pharaoh Akhenaten, Nefertiti,

and their children, an intimate family portrait unique to the Armana Period.

Early on it was clear that the total exchange of artifacts was not equal,

but more outrageous is the fact it has now been proved that the stela of the

royal family is a rather clumsy fake. Deepening the irony, Borchardt had gone

to great lengths to describe the fake as not only better than a similar one the

Germans had in Berlin, but also aesthetically superior to Nefertiti's bust.

Yale University and Peru's government remain locked in their long battle over the disposition of 40,000 artifacts removed from Machu Picchu from 1911-1915. Eliane Karp-Toledo, Peru's former first lady and archaeology lecturer at Stanford University, is a major critic of Yale's claim to the items, discovered by amateur archaeologist and later U.S. Senator Hiram Bingham.

At a talk at Yale last month Karp-Toledo presented excerpts from Bingham's letters in which he admitted that everything belonged to Peru and that the artifacts should be returned. This is the position of the National Geographic Society, which supported Bingham's three expeditions. Sen. Christopher Dodd also supports the repatriation of the objects from Machu Picchu.

A memorandum of understanding that was signed by both parties in 2007 (after Karp-Toledo's husband left office) now appears to be null and void because the Peruvian government has renewed legal action against Yale. Many Peruvians join Karp-Toledo in objecting to a provision in the memorandum that would allow Yale to keep those items "not of museum quality" for 99 years.

Yale claims that their experts need more time for research, but the Peruvians want to make their own evaluation of the objects. They are indignant that Yale's professors presume that only they can do research on others' cultural heritage.

The position that if some artifacts are returned then there will be a world-wide request for objects is alarmist, and it ignores the plain fact that only a few cultural treasures are in dispute. It is ironic that some advanced liberal democracies built on the rule of law and property rights are so stubborn.

Some say that the Lord Elgin saved the Parthenon Marbles from the acid rain of 20th Century Athens, but the Greek half of the frieze is in much better shape than the British half. British conservationists, seduced by the faux classical ideal of pure white marble, scraped off what remained of the original paint and the honey-colored patina of the Pentelic marble.

British public opinion has long held that the marbles should be returned, and a recent unscientific poll conducted by the Guardian found that 94 percent of its readers supported repatriation. At a February 2008 Cambridge debate on the issue the Greeks won by a vote of 114 to 46.

For many years British authorities rebuffed Australia's request that aboriginal remains be returned for proper burial. Finally, Tony Blair intervened and did the right thing. It's high time that Nefertiti's beautiful head goes back to Egypt, and that the two halves of the greatest symbol of democracy are reunited on the Acropolis.